A groundbreaking discovery from NASA’s Juno mission sheds new light on Io.

Others are reading now

NASA has revealed groundbreaking new information about Jupiter’s moon Io, solving a mystery that has puzzled scientists for over 40 years.

The Juno mission has provided insights into why Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, WP Tech reports.

Io: A Volcanic Wonder

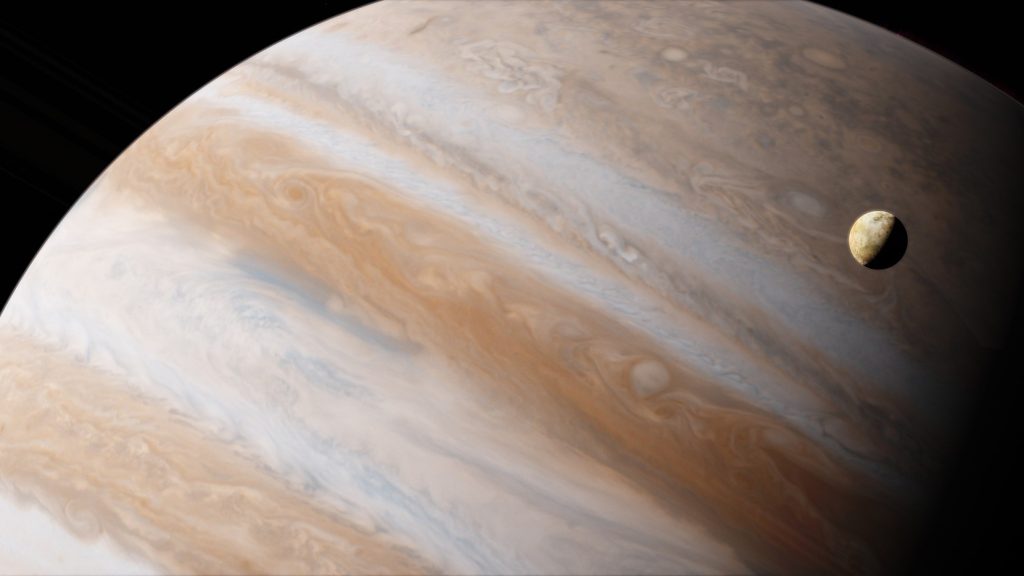

Io, Jupiter’s third-largest natural satellite, is about the same size as Earth’s Moon.

Its thin atmosphere, primarily composed of sulfur dioxide, gives the moon its striking yellow, orange, and red appearance, a result of its sulfur-covered surface.

Also read

Io is home to about 400 volcanoes, which eject lava and gases in nearly constant eruptions, making it the most volcanically active body in the solar system.

NASA has studied Io for nearly 44 years. Previously, scientists believed that a magma ocean beneath Io’s surface was responsible for its intense volcanic activity.

But recent findings from Juno have revealed that this theory is incorrect.

Volcanic activity on Io was first discovered in 1979 by NASA scientist Linda Morabito, who noticed volcanic plumes while analyzing images from the Voyager 1 probe.

Since then, researchers like Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute have worked to uncover the mechanisms driving Io’s volcanic eruptions.

In December 2023 and February 2024, the Juno spacecraft conducted close flybys of Io, coming within about 1,500 kilometers (900 miles). These observations have shed new light on Io’s unique internal processes.

Tidal Forces Drive Volcanic Activity

Io’s extreme volcanic activity is caused by its close proximity to Jupiter.

The moon’s elliptical orbit brings it closer and farther from the gas giant, causing changes in the gravitational force acting upon it. This results in tidal deformation, where the moon is constantly squeezed, generating internal heat through friction.

NASA scientists have determined that Io’s interior is likely mostly solid, and each volcano has its own localized magma chamber, unconnected to the others. Data from Juno and previous missions indicate there is no global magma ocean beneath Io’s surface.

“Juno’s discovery that tidal forces do not always lead to the formation of global magma oceans makes us rethink what we know about Io’s interior,” said lead researcher Ryan Park.

He added that this finding could also have implications for understanding other celestial bodies, such as Enceladus and Europa, as well as exoplanets like super-Earths.

“These new discoveries give us an opportunity to rethink what we know about planet formation and evolution,” Park explained.

NASA researchers are optimistic about further revelations from the Jupiter system.

On November 24, Juno completed its 66th flyby of Jupiter, and on December 27, the probe is set to make an exceptionally close approach to the planet, coming within about 3,500 kilometers (2,175 miles) of Jupiter’s cloud tops.